- Home

- Richard Dansky

Firefly Rain

Firefly Rain Read online

Is anybody there?

The hairs on the back of my neck were up, and I had the cold certainty in my gut that someone was standing right there, watching me.

“Hello?” I called, realizing that anyone who could answer was in the house uninvited and closer to the shotgun than I was.

No one answered, not my “hello” or my prayers. No floorboard creaked, no papers shuffled, nothing.

I was alone… with no one else in the house.

No one else alive in the house.…

Praise for Firefly Rain

“Remarkable… a supernatural thriller that effectively breathes life into one of the genre’s staples—the haunted house. Dansky convincingly portrays Logan’s isolation and terror, and subtly gives glimpses of the forces arrayed against him. The author’s insights into human nature and ease with expressive language bode well for future fiction from his pen.”

—Publishers Weekly(starred review)

“Dansky’s ability to build terror slowly and talent for hiding his clues in plain sight demonstrate an attraction to old-fashioned, classic horror. Dansky… exhibits his talent for original supernatural fiction in this tightly paced tale of mystery and terror.”

—Library Journal

“Page by page, Dansky builds the tension.… A quick, enjoyable read and the first sign of a new talent in the genre.”

—SF Site

This title is also available as an eBook

Firefly Rain

RICHARD DANSKY

Gallery Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2008 by Richard Dansky

Originally published in hardcover by Wizards of the Coast, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Gallery Books trade paperback edition April 2010

GALLERY and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or [email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Akasha Archer

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978-1-4391-4863-1

ISBN 978-1-4391-6327-6 (eBook)

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright Page

prologue

one

two

three

four

five

six

seven

eight

nine

ten

eleven

twelve

thirteen

fourteen

fifteen

sixteen

seventeen

eighteen

nineteen

twenty

twenty-one

twenty-two

twenty-three

Epilogue

Firefly Rain

prologue

I remember a night when I was six years old the way some folks remember their first kiss or the day a loved one died. Six years old and full of fire, wandering around the field behind the house with an empty jam jar in my hand. I caught my first firefly that night—pulled it out of the air just a little too hard and crushed the life out of it with fingers that shouldn’t have been able to do so. I didn’t know what I’d done, of course, so I took my prize and set it in the jar. It slid halfway down and then stuck to the side, its legs moving slowly, its gold-green glow fading to nothing.

“Shine,” I told it earnestly and screwed the cap of the jar on tight. I’d punched air holes in the top with scissors, the way I’d thought you were supposed to, and I figured that down in the jar the firefly could hear me. “Shine for me,” I told it.

“Son, don’t do that,” my father said. He was a large man who kept getting larger, with a shock of black hair that never got around to turning gray. Mother had broken him of smoking the year I turned five, but she’d never been able to stop him eating instead, and it showed from year to year. When I was six, though, he could still move like a cat, and I didn’t know he was behind me until I heard those words. “Don’t do that,” he said, and I turned to face him.

“Don’t do what?” I asked and held the jar up before me as an offering. “Want to see my firefly?”

He pushed my hands down gently. “No, son, I don’t. You shouldn’t catch them that way.”

“Why not? I made air holes,” I said and tapped on the lid of the jar for emphasis.

He took a deep breath. “Do you know why fireflies light up?” he asked.

“No,” I replied.

“It’s because they’re looking for other fireflies. The ones in the air are looking for the ones on the ground. See?” He pointed to a spot in the grass that was all alight. “That’s how they find one another. The ones that shine the brightest find the others the fastest. But if you catch the brightest, because they’re the ones you see the best, well, that means the best fireflies don’t get to meet their friends. And that’s wrong, you see?”

I stared up at him and blinked. “No,” I said. “I just want to catch fireflies.”

He opened his mouth to try to explain further, and Mother hushed him. “Let me explain, dear,” she said, and Father’s mouth shut like a shed door swinging closed.

“Of course, dear,” he said, and he walked off. She watched him go without saying a word, then turned back to me.

“The problem isn’t with you wanting to catch fireflies, you know,” she told me as she bent down to put her face near mine. Her voice was a whisper that just the two of us shared, her face a blur in the evening darkness.

“Oh?” I said. “Then why is Daddy upset?”

“He’s not upset. He just doesn’t want you to keep the fireflies from doing what they have to do,” she said. “You see, fireflies are how angels find things when they come down from heaven. If you catch the fireflies, then the angels get lost and they can’t take the good souls back to Heaven with them. That’s why you can’t catch fireflies, honey. Is that okay?”

I nodded at her, my eyes wide. “Can I still chase them if I don’t catch them? Is that all right?”

She kissed me on the forehead and laughed. “Of course, sweetheart. Of course that’s all right.” Then she took the jar from me, unscrewed the lid and gently shook the dimming corpse of the firefly onto the grass. Then she screwed the lid back on and headed for the back door to the house, her brown dress making her almost shapeless in the twilight.

My father caught up with her right outside the door. I could hear their voices rising, each in turn, but I paid no attention to their words.

I was too busy chasing fireflies.

one

Dear Son,

Your mother just informed me of your intention not to return home for the holiday season, and I have to say, I am disappointed in you.

I’m sure you have plenty of reasons that seem good to stay at school over Christmas.

You have your friend, you have a life up there, you maybe even have a girl. I don’t know—these aren’t things you’ve shared with us since you’ve been away. I can understand wanting your own place and your own life, and I’m sure the house where you grew up seems boring and quiet compared to all of the excitement of the big city, but it’s where you came from, and that ought to mean something to you, at least at Christmas.

I have a certain amount of sympathy for wanting to find something of your own, especially at your age, but that should never come at the cost of causing pain to others, especially not those who love you. I cannot count the number of times you’ve promised your mother that you would be home for Christmas this year. Needless to say, she misses you terribly, and the news that you are not coming home has hurt her badly.

You’re a grown man now, or close to it, and I’m sure you think you can make your own decisions. Part of being a man, though, is understanding those decisions, and weighing what they cost. There’s more in this world than you and your wants, son. You’d do well to remember that.

We’ll leave a place for you at the table, just in case you change your mind. Your mother would be pleased if you did.

Father hadn’t signed the letter, hadn’t needed to, really. There was no one else it could have come from. I’d read it when it had first arrived, then I’d tucked it away in a place where I couldn’t find it easily when the mood struck me to throw it away.

And now, here I was holding it in my hands, the last thing that was mine in a place I’d lived in for years without leaving any kind of mark. I was leaving, heading back to Carolina with my tail between my legs and the memory of a failed business behind me. It was time to go somewhere else, to regroup and recover.

Even if that meant going back to a place I thought I’d never see again. In Boston, the wounds were too fresh, the failure too new. Distance was needed. It would just be a temporary visit, I told myself. I’d be in and out, recharged and ready to take on the world again, somewhere else.

So my belongings, the few I’d wanted to keep, had gone on a moving truck headed south, and here I was ready to follow. “A retreat,” a former employee of mine had called it, and she’d been right. I was falling back.

The letter was still in my hands. I felt the rasp of the paper under my fingers—old, heavy typing paper that hadn’t aged well. It was dry and brittle, and carried with it an unpleasant weight of memory and expectation. It was the last letter Father had ever sent me, and the notion of bearing it back to its point of origin seemed suddenly, deeply wrong.

I crumpled it up and threw it on the floor. Then I turned out the lights, hung my key on a hook over the kitchen sink, and went out to where my car—and the road back to Carolina—waited for me.

That letter had been written on the occasion of my not coming home for Christmas my junior year of college. It was the first time I’d felt brave enough to stay away, to make sure that miles stayed between me and that house, that land. It wasn’t that I hated my parents. I loved them both, and they’d loved each other, but in a way that had cost them for loving. I’d never really fit in that house, and living there had been like being stretched over a too-tight frame.

Father’d died six years after sending that letter, five years after I’d graduated and announced I’d be staying in Boston for good. It was his heart that had finally given out, but I had to figure the rest of his organs had been just disappointed they’d lost the race. Liver, lungs, kidneys—the doctors told me they were lined up one after another, ready and willing to go.

Mother went ten years after Father’s passing. I think I was partially to blame for that, though no one ever said as much to my face. My visits home grew shorter and shorter, and I made them less and less often. There was a business to run, after all, and quiet evenings in North Carolina farm country didn’t offer much compared to the nightlife on Lansdowne Street. Besides, there was always a sense of expectation when I did make it home, an unspoken question hovering in the air of when I was going to come back for good. Mother never asked, so I didn’t have to answer, but it hung there between us every time.

I nearly missed her funeral because we were closing a deal for distribution with some Japanese firm that week and they wanted me there for the signing. There would be plenty of time to make it back after the meeting, I told myself, and I almost believed it.

In my darker hours, I wonder if Mother deliberately chose that moment to die, to see if just once I’d choose her over whatever it was I’d found up north. As it was, it was a near thing, and I made it home with only hours to spare. I remember driving like a madman from the airport in a rented car that was too big for my needs and too slow for my wants, but which had been the only one left on the lot. I also remember cursing everyone and everything else for my lateness.

They buried her out back, next to Father but with enough space between them that it was clear they didn’t always see eye to eye. Afterward, we gathered at the house, to share memories and reassure one another that we wouldn’t forget her. Friends of the family asked me a dozen times and more if I was all right, if there was anything I needed, if there was anything they could do. I thanked them all, told them gravely that I was fine, and promised them I wouldn’t sell the property. “Family land stays in the family,” I told them, and I’m pretty sure I meant it. And since there was no other family, no aunts or uncles or cousins out there to maybe cast their eyes on the property, that meant it stayed with me.

Before the last of the well-wishers drifted away, I made arrangements with a man named Carl Powell, a friend of Mother’s, to serve as caretaker on the property in my absence. Carl was weathered and lean, and I couldn’t even guess how old he was. He still had all his teeth and most of his hair, and he’d been an occasional visitor at the house for as long as I could remember. I knew that he had been a big help to Mother in her declining years, and I felt good giving him the key and a check to cover the first year’s worth of maintenance.

“Keep your money,” he’d told me at first, when I’d asked him if he was willing.

“Carl, it’s an old house, and it’s going to need some work,” I replied. “And it’s a fifteen-mile drive for you to get here from your place. I can’t not give you money for doing this.”

“Fine,” he said, but there wasn’t a lot of joy in his voice. “I’ll give you an accounting at the end of the year.”

“I trust you,” I said, which was probably the worst thing I could have said. “Let me know if you need any more.”

“I will,” he said in a voice that promised just the opposite, and he stuffed the check into his pocket. Carl left without another word to me, and hardly any to anyone else.

Reverend Trotter, an old family friend, was the last to leave. He’d given a fine and gentle eulogy for Mother, and he’d been sharp enough to make sure I didn’t have to speak more than a few words about her. Like everyone else in that church, he knew that a few words were all I had.

“Jacob,” he told me, and he wrapped his hands around mine, “the times ahead are going to be harder than you think. You’ve lost both parents now, and that’s the sort of thing that hits a good man hard. If there’s anything you need, or if you just have to talk to someone, don’t hesitate to call.”

“Thank you, Reverend.” I squeezed his hands for a moment, then pulled mine away. “I think I’ll be all right, though.”

He gave me a look that said, clear as day, he didn’t believe me. “That’s a big house full of memories you’ll be staying in, Mr. Logan, and those memories just might come knocking harder than you think. I don’t like to think of you out here by your lonesome in the middle of the night, realizing deep down that she’s gone and you’ve got things you never had a chance to say.”

I smiled at him. “Don’t worry, there’s no chance of that. I have to go back to Boston. I’m leaving the day after tomorrow.”

He blinked and took a step back. “So soon? You sure you don’t need more time here, just to pull yourself together?�

�� He leaned in close and added conspiratorially, “Besides, some folks might take that as disrespectful.”

My smile got a little harder. “I know how to show respect for Mother, Reverend. Other folks can say what they like. Carl Powell’s going to be taking care of the house, and I’m better equipped to handle the legal paperwork back home. Staying here wouldn’t do anyone much good.”

“Staying home might do you more good than you think,” he corrected me, then shook his head. “I’m sorry, I’m speaking out of turn. Chalk it up to worry, Jacob. That offer stands, even if you have to call me from the big city in the middle of the night.”

I held the door open for him. “I do appreciate that, Reverend. Thank you.”

“You’re welcome. You take care of yourself, Jacob Logan. Come back sometime.” He walked across the porch and down to his car without looking back, without expecting an answer.

“Some time,” I said softly, after he’d gotten in his car and driven off. The sun was going down as he did so, and long shadows marked my way as I walked back down to where they’d buried Mother. As the sky got darker, the fireflies came out to light my way.

I sat down there by the graves and waited, reading the inscriptions on the headstones a dozen times and wondering why I wasn’t feeling more. It wasn’t until full dark came that I finally stood and wiped the stones clean of the fireflies that landed on them in their hundreds, one by one by one.

Only then did I walk away.

The drive took two days. I could have made it in one but didn’t see the need. The truck with the rest of my belongings was following well behind, following the sort of route that let it leave earlier and arrive later than I would, without any way to check on it in between. In practical terms, that meant that there wasn’t any sort of schedule for me to keep, which was the sort of practicality I liked. I hadn’t called ahead to let Carl know I was coming, and I liked it that way. There was a vague notion in my head of drifting back into town and making as light an impression as possible. Maybe I could be gone before anyone noticed I’d come.

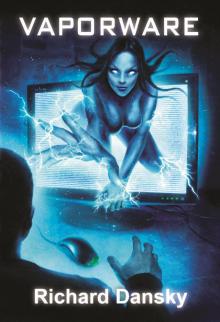

Vaporware

Vaporware Firefly Rain

Firefly Rain