- Home

- Richard Dansky

Firefly Rain Page 11

Firefly Rain Read online

Page 11

Heading down the road the other way, of course, was simply not an option.

Which left me with the Thicket, and in truth, that was just fine with me. It was a still place, a private place, and it was far more mine than the house could ever be. Neither Mother nor Father, nor anyone else, now that I thought about it, had ever spent any real time down there. Which meant that it was nobody’s, and if it was nobody’s, then for a little while I could make it mine.

Whistling a song I’d heard on the radio on the drive down—something about a cheating woman and an angry man, not that I could blame her for running around on a man who sounded like that—I made my way down from the house and past the curtain of pines by my parents’ markers. The urge to look at the gravestones was strong, but I resisted. That wasn’t why I was out there. Besides, paying my respects with the shotgun in hand seemed a mite disrespectful, all things considered.

Instead, I focused my eyes on the Thicket looming up ahead. The sun was well up, but that just made the shadows darker under the gathering trees. A little wind was coming in from the west, just enough to make the grass bow down before it while the other weeds stood tall. Birdcalls came from every direction. They sounded surprised, like they didn’t expect a human down here on this part of the land. Come to think of it, they probably didn’t.

A few more seconds of walking and scanning found me what I was looking for. While it had been rare for deer to get up near the house on their own, occasionally Mother had put a salt lick up behind the house. Then they’d beaten a path to our door, one after another. Sometimes we’d had a half-dozen or so just milling around back there, and in their coming and going they’d trampled a few routes into the Thicket pretty thoroughly.

I had a hunch that since Mother had done it back in the day, Carl had kept it up after she died. Sure enough, there was a game path cutting through the scrub at an angle, and it was easy to find where it came out. After all, there was no sense walking through the stickerbushes if I didn’t have to. Letting the deer do the work for me was the sensible thing to do.

The dead weeds made a soft crunch under my feet once I moved onto the deer path. It ran pretty straight back toward the cover of the trees, intersected here and there by other trails that led off toward whatever the hell deer found interesting. I ignored the trails and headed toward the line of trees. Already I was passing the outliers, pickets standing watch for the rest of the forest. They were thin trees, but wiry, growing up fast. They had probably only been there for fifteen years, but they looked like they’d been there a century.

Still, my business, if indeed I had any, was farther back. It wasn’t that I had any particular memories of the Thicket from my childhood. I hadn’t had a tree house, a secret place, or a rock fort tucked into the heart of the woods. It was just the Thicket, the part of the land that wasn’t the house and wasn’t in sight of it, and that’s what I needed.

Something scuttled through the grass to my left, and instinctively I moved the gun into a good firing position. The sound moved away, no doubt a rabbit that saw a trespasser a couple times its size and wanted no part of it. I paused for a moment, listening for further movement, but didn’t hear any. Up above, a red-tailed hawk circled silently; in the trees, his songbird cousins made noise; and the grass whispered with the wind. No footsteps, though, no footfalls or rustling through the grass.

“Perfectly goddamned normal,” I said, but as I started walking again, I kept the gun ready. The house had already disappeared back behind that first wall of trees, but now those were vanishing as well, hidden by a new line of green. Up ahead, the pines were getting thicker, promising less scrub on the ground and more shade overhead. It was as good a reason as any to pick up the pace, so I did.

A rustle of squirrels in the branches announced my arrival in what looked to be the Thicket proper. It was young forest, I could see. None of the trees were more than four or five inches thick, and the cover of needles and leaves on the ground was patchy. Here and there, shrubs and weeds defended bare spots in the soil, often in places where beams of sunlight found their way through the leaves overhead. Vines wound their way up a few trunks: poison ivy, thankfully, not kudzu.

I took a deep breath, surprised to find myself relaxing just a little bit. The woods felt good in a way the house hadn’t, and I could feel myself responding. They felt friendly in a way a lot of woods I’d been in hadn’t. The trees were still far enough apart that a man could walk easily, not crowding against each other. You got the feeling in old woods that you were intruding on the trees’ business, like as soon as you left, they’d go back to pushing and shoving and fighting for sunlight, and they were mighty annoyed with you for making them stop for just a minute. Here, they were just starting to figure that out, and the air hadn’t gotten toxic with it yet. It felt nine kinds of fine.

I kept the shotgun ready, though, and I didn’t flick the safety on.

Somewhere farther on, a woodpecker took aim at a tree trunk and went to work. The sound echoed under the leaves—ratta-tatta-tatta-tat, ratta-tatta-tatta-tat. It seemed like as good a direction as any, so I made a guess as to the source of the sound and headed off toward it. The slope of the land evened out a bit and the shade got darker. It was cool under the leaves, even with the trees keeping out the breeze. All around me, I could hear things moving away—running for cover in the dead leaves, scuttling up tree trunks, flapping away. The woodpecker kept going, though, the sound stronger than ever, so I let it pull me along and stopped wondering about anything else hiding in the woods. The leaves crunched under the soles of my sneakers. I tried walking quietly but gave up that idea in about a minute flat; the woods themselves were having none of it. You couldn’t take a half-dozen steps in any direction without making noise—a crunch for the leaves or a quieter whoosh for the pine needles. Where they mixed, you got both put together and louder than either.

The ratta-tatta-tat stopped. Up overhead, there was an explosion of wings and leaves. I caught a glimpse of the bird—red head, white beak, black and white body—as it leaped from the tree in search of what I guessed was a less busy place to dine. So help me, the damn thing looked offended that I’d interrupted it.

“Be thankful I don’t charge you rent,” I called out after it, though I’m reasonably sure it didn’t listen. The woods swallowed my words in just the way they hadn’t chewed up the woodpecker sounds, and left me standing there in silence.

Maybe twenty yards off, I heard the sound of footsteps on leaves.

I didn’t think, which is probably for the best. Instead, I pressed my back against the tree, putting it between me and whatever—whoever—had taken that step. The shotgun I held ready. I could feel the sweat on my fingers.

Probably just a deer, I told myself, waiting for another footstep. Probably just a goddamn wild animal, doing exactly what it’s supposed to here in the goddamned Thicket.

But I didn’t believe that, even as I mouthed the words.

Another footstep announced itself. It was cautious and slow, like a man putting his heel down first and rolling toward the toe. Like a man trying to walk quiet on a carpet of leaves.

I breathed shallowly, trying to make as little noise as possible. My right hand held the stock, my left the barrel, and the gun was pulled close to my body, to make sure there wasn’t any shine off it. Each breath made a cloud of moisture on the steel of the barrel that faded away in a heartbeat.

More footsteps, some on leaves, some softer on exposed dirt. The snap of a twig came across like a whip crack, and I could feel my finger squeeze involuntarily on the lead trigger.

All around us, the squirrels and the birds went about their business, calling back and forth and generally oblivious to the fact that someone was stalking someone else in the heart of the Thicket. The problem was, I couldn’t figure out who was stalking whom.

The footsteps got a hair louder and a touch closer. My heart pounded, the blood in my ears almost as loud as the sound of footfall on forest floor. Another step,

a crunch so close I could swear it was right in front of me.

And then nothing.

I counted to ten. To twenty. Told myself that he—whoever he was—was probably waiting for me to show myself. Counted to thirty, then counted down backward. There was no sound of movement, no sound of breath moving in and out.

“Damn fool,” I whispered, and I rolled out from behind the tree to see who waited for me.

“You need to pick a thicker tree to hide behind, boy,” said Carl from behind me. “You were showing on both sides.”

Before he was done speaking, I spun and brought the gun down like it was the most natural thing in the world. He was faster, though, his hand coming down to knock it low and away.

I tell myself that it was the shock of his hand against the barrel that nudged my finger hard against that trigger. Sometimes, I even believe it—that I wasn’t about to shoot him in the gut without thought or apology.

Doesn’t really matter now, I suppose. He slapped the barrel out of line and my finger closed on the trigger and a load of #6 came screaming out of the shotgun with a sound like mountains coming down.

Two trees went down, young ones sawed off about a foot off the ground by the buckshot. The sound punched my ears and the kick of the gun drove the stock into my belly hard enough to make me grunt. All around, animals scattered like water on a hot skillet, calling out warnings and running as fast as they could. Ragged furrows appeared in the earth, showing the red clay hiding under the soil. Leaves kicked up by the shot danced in the air, slowly coming down to hide the scars I’d inflicted.

And Carl, for his part, stood there like a man carved from wood and stone, watching me watch what I’d done.

“You need to be more careful with a piece like that,” he said when I stopped blinking. “’Specially when you’re not used to guns. Someone might get hurt by accident.”

I looked at him. He seemed calm, his voice mild, as if he’d been telling me I was holding a hacksaw the wrong way going after a tree branch. He was wearing a blue button-down work shirt and jeans, brown boots, and a hat that might have said John Deere back when it had been green instead of gray with age and use. It was all perfectly normal, really, except that he had no business being in the woods on the ass end of my property in the middle of the day.

That, and the fact that no man I’d ever seen could have moved the way he just had.

“Afternoon, Carl,” I finally said when I figured my voice wouldn’t crack. “Nice day for a walk, isn’t it?”

“Tolerable enough,” he agreed, and he nodded back toward the heart of the Thicket. “There’s something back here y’need to see.” He turned and took a few steps deeper into the woods.

I didn’t follow.

“No,” I said.

He stopped, turned, and looked over his shoulder. “No?”

I laid the gun down and crossed my arms. “No. Not until you tell me what the hell you’re doing here, Carl. Not until you tell me what’s going on.”

His face screwed up like fruit left out too long in the sun. “You ask a lot of questions for a man who won’t look for answers, son. I’m trying to show you.”

I shook my head. “No, you’re not. You’re asking me to follow you on your say-so after I find you out here in the middle of the day for no good reason. I don’t even know how the hell you got here, and I’ve half a mind to march back to the house to call Hanratty.”

He cracked a smile. “You could do that, I suppose. Wouldn’t do you much good. Time you got back to the house and called and she told you to calm yourself down, and you threw enough of a fit to get her out here, I’d be long gone. And don’t be thinking you’ve got it in you to drag me back to the house, boy. Not on your best day.”

I sat down. “Maybe. But you’ve got something you want to show me. All I have to do is sit here and you’re screwed.”

“I’m trying to help you, boy,” he said, and it was like he was looking down the barrel of a gun and pulling the trigger. The words came out like bullets, one after another. “You come back here and you know nothing, nothing at all about what’s going on, and yet you got your smart mouth and your stupid ideas, and you go around sticking your tallywhacker into every damn hornet’s nest you can find. This is bigger than you, you know. There’s other people waiting on you to get your head out of your ass, but it seems plain to me we’re gonna be waiting a long damn time. You can think on that while you sit there, if’n you want. I’ll be back in a month or two to see if you’ve grown up any.” And then, he shut right back down and started walking away.

“Wait,” I said. He didn’t.

I stood. “Carl. Wait!” He kept walking.

“Carl!”

He stopped and turned halfway around with a look that could sour milk.

“Yes?” was all he said.

“Two questions,” I said. “Answer those two, and I’ll follow you, I swear.”

He considered it for a moment. “The answers you get might be ‘go to hell,’ you know.”

I gnawed my lower lip. “I know,” I said. “It’s a good enough answer for me.”

“Fine.” He stood there, arms crossed on his chest. “What’s so all-fired important to know that you’ll jump up and follow me into the dark of the woods if I tell you, when you wouldn’t pay me no heed before?”

I swallowed and took a deep breath. “You said before you were keeping a promise. What’s the promise?”

He chewed the air as he considered the question. “None of your damn business,” he said finally. “Though it’s a sensible question for you to be asking. What’s the other one?”

“How the hell did you get back here?” I asked.

He grinned. “Walked on over from the Tolliver property. Damn fool waste of a question, if’n you ask me.”

And with that, he headed back into the deep part of the Thicket. Grabbing the shotgun in my off hand, I followed him.

I was thoroughly lost by the time Carl led me to our destination. I knew the Thicket was big—I’d seen the acreage of the property on the deed, after all—but it’s one thing to see it as a number on a piece of paper, another to actually walk it without a hell of a lot of faith in where you’re going.

The walk itself took maybe twenty minutes, though I couldn’t tell you which direction we’d gone in or if we’d just hiked in a big circle. A couple of times I asked Carl how far we were from where we were going, and he didn’t answer. Come to think of it, that’s not quite true. One time, he grunted, and another he shot me a look. Neither was what you’d call real helpful.

Finally, we came through a thick stand of trees into a little bit of a clearing. Carl took a few steps in, then turned and stopped.

“This is it,” he said. “It’s where I needed to bring you.”

I stopped, too, right on the edge of the opening in the trees. A couple of feet between me and Carl still didn’t seem like a bad thing, though I also figured that if he really wanted to do me harm, there wasn’t much I could do to stop him. So I did the next best thing and looked around.

The clearing was maybe thirty feet across, shaped more or less like a circle. The trees that ringed it were among the tallest and, if I had to guess, the oldest in the Thicket. There was barely space enough between them to pass through.

The floor of the clearing was covered in greenery, most of it ferns and the like. Nothing was more than a foot or so tall, and I didn’t see any saplings growing out there. A gap in the foliage overhead let the sun beat down on it, and despite myself, I was impressed.

“Very nice, Carl,” I said, and I leaned up against the nearest tree. Sweat dripped off my forehead, and my arms had started to ache from lugging the damn shotgun around with me. “So what is this place?”

“It’s where everything else ain’t,” he replied, and he took a couple of steps back toward the center. “Come on closer. It ain’t gonna bite you none.”

“You sure?” I said, and I looked around, left to right. There was nothing but greene

ry and Carl, but neither looked particularly threatening at the moment. So I shot a short prayer straight up through the trees, then walked out to join him.

He wasn’t smiling when I reached him, but he wasn’t frowning, neither, which I regarded as a small victory. “I’m here, Carl,” I said to him. “Talk to me.”

“I’ll tell you what I can,” he said, and he scratched the back of his head. “I can talk to you here, I think.”

I think? Uncertainty from Carl was a new thing to me, and I looked around again to see where it might have grown from. There was nothing strange that met the eye, but I’d been saying that a lot lately.

“What’s so special about this place?” I asked. “I mean, there’s no trees, but there are a lot of places in Carolina these days that don’t have any trees. Of course, this one doesn’t have a mall being built on it, so I guess that makes it different.”

Carl shook his head. “For a minute, I thought I’d gotten through to you, but I see I was mistaken. You spent too much time in that city, boy. Too much time forgetting who you are and where you came from.”

My temper started rising when he said that, and I shoved it back down as best I could. “That’s not fair, Carl. I am who I am. I’m from here just as sure as anything else.”

“No.” He shook his head. “You were born here. But you ain’t from here. You decided not to be a long time ago.”

I could feel my face getting red, and I could see that Carl saw it, too. “Give me a break. I’m not the only kid who left this town to go to college.”

“You’re reading it too simple. You’re right, you ain’t the only one to go. But some of them came back and chose to be here. And some left for good and never looked back. But then there’s you.”

I squinted at him. “And then there’s me what?”

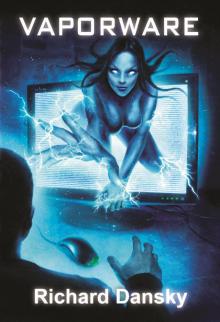

Vaporware

Vaporware Firefly Rain

Firefly Rain