- Home

- Richard Dansky

Firefly Rain Page 16

Firefly Rain Read online

Page 16

“Hmm,” I said, and I studied the picture. “She seems… determined.”

“Even more so now,” the librarian agreed. “You do want to be on her good side.”

“It’s too late for that, I’m afraid.” I skimmed the article. There was a lot about how Maryfield was very happy to have two new officers with experience in the Durham County Sheriff’s Office and police departments. They were out here as part of a new state initiative to share expertise with rural police departments, blah blah blah, and nothing more useful. There were absolutely no biographical details on either one of them, except that vague mention of their previous employment.

That had me curious.

“Read enough?” Miss Moore asked. “I’m afraid there isn’t much else to see, at least not in the Administrator. When Officer Lee left, it was regarded as tasteless to report on it. There’s maybe a column inch or two, but it’s buried a couple of pages in. No pictures, of course.”

“Of course.” I turned to her. “When did that happen?”

She shrugged. “About two years ago. That’s also when she, well, it’s just not polite to talk about that sort of thing.”

I thought about the woman I’d seen in the picture, then compared it to the police officer who’d sat in my bedroom and told me how Carl had helped save my life. “I understand, I think.” With a click, I disengaged the reader and rewound the film. “I think I’m going to need to switch to the N&O. You don’t have the Durham Herald-Sun by any chance, do you?”

“I’m afraid not.” With a shake of her head that didn’t dislodge her bun one little bit, she pulled the microfilm out and shut the reader down. “Give me a minute to put these away. I’ll meet you at the microfiche reader.”

“I’ll bet you will,” I said in my best Groucho Marx, and then I cringed when she gave me a look of noncomprehension. “Never mind. And again, thank you.”

“You keep thanking me like that,” she said as she slammed one drawer shut and opened another one, “and I might get the wrong idea about why you’re down here. There’s such a thing as being too polite, you know.” Before I could say anything in response, she held up a manila sleeve with half a dozen sheets of microfiche in it. “Start looking in here. I’ll be upstairs if you need me. It’s not likely anyone else will be in today, but if the head librarian stops by, she does like to see me at the front desk.”

She slammed the drawer shut and locked it and was halfway back to the stairs before she remembered she was still holding the microfiche. I got up out of my chair to take it from her and, accidentally, my fingertips brushed hers. Our glances locked again, and this time I couldn’t look away.

“Well,” she said, and she let go of the envelope. Before I could say a word, she was back upstairs, and the door had slammed shut behind her.

“Idiot,” I groaned to myself, and I sat back down. The fiche reader was actually simpler than the film reader was, for which I was most appreciative. Shaking hands aren’t good for working machinery, at least not if you want the damn thing to work.

With a look at the closed door, I slid the first sheet of microfiche in and flipped the machine on. The News and Observer was an order of magnitude thicker than the Administrator, but some kind soul had chopped it up into sections that let me scan it faster.

On the fourth sheet I found what I was looking for. In black and white, it read “Sheriff’s Office Scandal Probed,” and underneath was a picture of a very unhappy-looking Sheriff’s Deputy Jeremiah Lee. The article danced around words like “financial improprieties” and “prisoner mistreatment” in a way that left no doubt that there was a fine stink that had settled over the whole affair.

Once I’d located the first article, the trail was easy to pick up. More allegations here, witnesses coming forward there, and then, abruptly, the end. March of 2002 brought a resignation, a short notice, and a disappearance. It looked as if Deputy Lee had cut a deal and left town as part of it. No doubt his wife had resigned her post and followed him.

It made sense, really. Getting away from the big city and burying themselves in a small town that wasn’t likely to know much about what Deputy Lee might or might not have done was perfectly sensible. And if the rural police assistance program was invoked as a justification, there was even less reason for people to ask questions.

No wonder Hanratty—I couldn’t think of her as Lee, no matter how I tried—looked so grim in that photo. This wasn’t something she’d planned on doing, or even wanted to do. But she’d done it anyway, and stuck to it even when the man who’d brought her here had wanted to go.

There was something admirable in that, and also something sad. One of these days, I’d have to figure out the balance.

A quick look at my watch told me that it was getting on time to meet Sam back at his truck, so I tucked the microfiche back in its sleeve and shut the machine off. It had been a productive day, and I’d gotten a lot to think about. Heading back to the house to do that thinking seemed like an excellent idea.

The lights went out.

“What the hell?” I asked, and I froze. The basement was pitch black. No light came in down the stairs, not even under the door.

“Well, God damn it,” I said. Immediately my hand went to my mouth, as if to keep any more cussing from leaking out where the librarian could hear it.

I sat in the dark and the quiet for a second, then flicked the fiche reader back on so I could see by the glow of the screen.

Nothing.

“First brownout of the year. Just my luck.” Carefully, I put the fiche down and shuffled my way over toward the stairs. The dark felt heavy, pressing in on my eyes like it wanted to blot out even the memory of light, and the air that carried it was no better. With the air-conditioning out, it had a sluggish weight to it, soaking up heat and smell and God knows what else until every breath felt like sucking weak tea through a straw.

Every few steps I banged into a chair or table, imaginary sparks of pain lighting up nothing but the space behind my eyes. I took each collision as a sign that someone wasn’t happy with me, as well as evidence I was going the wrong way. And so I took small, shuffling steps in small, shuffling circles, praying that sooner or later I’d hit the stairs or something like them.

Even the emergency exit sign was out, which worried me more than I would have liked to admit. Moving slowly, I advanced.

Somewhere between ten seconds and ten hours later, I found the banister. Leaning on it like a drunk with his new best friend, I called up the stairs. “Hello? Miss Moore? Could I get a flashlight or something down here?”

I got silence back, silence and a sense of deepening gloom. “Ah, hell,” I told the darkness, and I felt for the first step with my foot.

I couldn’t find it.

I tried again, more frantic. Nothing was there. It was as if the banister led up into nothingness, resting on thin air.

But that was impossible. It had to be resting on something, or at least that’s what the logical center of my mind told me.

Of course, it was also working overtime to remind me that the stairs had been there a minute ago, before the lights had gone out.

“Don’t panic,” I breathed. “You’ll be fine. There’s nothing to worry about.” I took a deep breath, held it, let it out. “The stairs are there. You just missed them, that’s all. Now let’s try again.”

Slowly, I dropped down to my knees, sliding my left hand down the banister post. It went all the way down the bottom, and I nearly let out a sob when my fingers found the junction between metal and carpet. Steeling myself, I slid my hand to the right, tracing the bottom of the post in hopes of crossing the boundary to that first stair.

It wasn’t there. The banister was just next to nothing. I pushed forward, and nothing stopped my hand. There was no way out of the basement.

I fell back, rolled, got myself onto hands and knees. The floor still felt solid enough, and I needed that. Full of fear, I crawled backward, away from where I thought the steps used to be.

The basement was crowded, after all. I’d bump into a chair or a table or wall soon enough. I’d find something solid as an anchor.

Two steps back. Four. Six. My breath had a rasping edge to it now, like I’d been running hard.

Eight steps. Still nothing.

“Hello?” I called out. “Somebody? Anybody! Can you hear me?”

No voice answered me. Two more steps, slower now, from the fear of not finding anything. Two after that, even slower. I felt nothing behind me, nothing to the side. There was just the darkness and the rough nap of the carpet under my bare hands, and that was all.

Suddenly, I was aware of light.

Not bright light. It was the twilight you get an hour before dawn, when the first rays of the sun are just starting to think about coming over the horizon, the light you’re not sure you’re actually seeing.

I blinked. The light was still there, and it was coming from all around me. Overhead, the lights remained invisible in the shadows. This light came from somewhere else, from the walls and from the air.

Ever so slightly, it got a bit brighter, almost bright enough to see my hand in front of my face. I froze, sat back, looked around. Yes, I was sure of it now. The light was growing. Not steadily, though. It surged and pulsed, one side of the room momentarily brighter than the other, then going almost completely dark while a ripple of dim lightning darted across the opposite wall.

Green-gold lightning.

“Oh, no,” I breathed. “Not here. Not now. Not possible.”

All around me, the light grew, and now I could see it for what it was. A living blanket of fireflies covered the walls, swarming up to the ceiling and down to the floor. Patterns of light danced around faster than the eye could see, just leaving the impression that I’d missed something vitally important. No light reflected from the ceiling, though, and no light shone on it. It was as if it was simply gone, torn away by the light.

I didn’t dare look at the floor. I could feel it beneath me, and that was as much as I wanted to know.

The furniture was gone now, too. Fireflies swarmed under it, and beneath their glow it just melted away. The banister still stood, I saw, leading up into infinity, but the stairs next to it were definitely gone. I didn’t want to speculate as to where they’d disappeared to, but I didn’t want to go there myself.

And now the fireflies were settling on me.

“Please,” I said. “No.” Not yelling, not screaming, just a quiet little request. Calm rained down on me, keeping me from crying out or defending myself. The universe was telling me this was inevitable.

More of them landed on me. I raised my hands, palms out, and a knot of golden light spun down into each one.

“Please,” I said. “Not here. Let me go home.”

I could feel them in my hair, crawling on my back, on my calves and down my arms.

“I’m going home now, I swear. Just let me go.”

They were tickling their way up my neck, burrowing in my hair, forcing themselves into my mouth. Others covered my eyes, found their way up my nose, dived into my ears. They went down my throat, filling me up, and more kept coming. I was glowing from the inside now, filled with light that sputtered and sparked and made waves of itself all through me.

No, I thought. Not like this. Panic arrived late but in a hurry, driving me to try to stand, to crash myself against the wall, to scrape as many as I could off me. It was too late, though. There were fireflies under my skin, flowing through my veins, glowing in time with my heartbeat.

Then everything was a green-gold light that swallowed me up.

“Mr. Logan? I hate to bother you, Mr. Logan, but we’re closing in five minutes, and I need to clean up down here.”

I started violently and looked around. The basement was as I’d remembered it, ceiling and staircase intact. In front of me, the microfiche reader sat, squat and ugly and most definitely there. Overhead, the fluorescent lights flickered and shone, all save a single burned-out tube on the other side of the room.

There were no fireflies anywhere in sight—living, dead, or imaginary. Miss Moore, on the other hand, was standing at the foot of the stairs, tapping her foot impatiently and looking pleasantly irritated.

“Excuse me? I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to stay this long.” I stood, then I felt my knees go weak and reached out for the chair to support me.

Her expression changed in a heartbeat. “Are you all right?”

I nodded. “Just recovering from a few bad days. I’m sorry I took so much of your time. I really didn’t mean to.”

“It’s perfectly fine. That’s why I’m here.” She crossed the room to where I more or less stood, then took the microfiche folder in her hand. “Let me just put this away, and then I’ll help you up the stairs. You look a bit peaked.”

I waved her off. “No, no, I’ll be fine. Really. As long as the banister’s there.” I took a quick peek at my watch and winced. “Oh, hell, the guy giving me a ride back must be pissed off.”

“Oh.” She looked embarrassed. “Sam Fuller actually came by looking for you. That was who you were referring to, right? He poked his head in and asked where you were. I told him that you seemed intent on what you were doing, and that I’d take you home.” She blushed, or seemed to in the pale white light. “He seemed kind of relieved, to tell the truth. I guess he was in a hurry.”

“His dog and I don’t get along,” I said, which was true enough as it went. “And thank you. You really don’t need to do this, you know. I can walk back.”

She looked down her nose at me. “Mr. Logan, you don’t look as if you can walk across this room. I’m certainly not going to let you walk however many miles it is back to your farm.”

“House,” I corrected her, even as I took slow, careful steps across the basement. “It hasn’t been farmed in years.”

“Well then, your house.” She dropped the fiche cards into the appropriate drawer and turned the key on it. “And the farm it’s sitting on. Now you go on upstairs and sit in the reading area. I’m sure you can find something to read while you’re waiting. It won’t take me but a minute to take care of all this. After all, you’re the first person we’ve had down here in three weeks.”

I thought about arguing, but only for a moment. “You’re the boss,” I said, and I hauled myself up the stairs. Behind me, I could hear her tidying up in mysterious ways that, near as I could tell, involved rearranging the chairs and pulling plugs out of walls. It was her business, though, so I didn’t speculate on it too much.

The chairs around that low, round table that made up the reading area were a little too comfortable. I sank into one like a frog on a too-small lily pad, reaching like a drowning man for one of the magazines on the nearby table. My fingers closed on one and I pulled it in, realizing I was looking at the back-page ad.

I called myself a dumbass, then flipped it around. The cover of Carolina Woman stared back at me, telling me that the ten most romantic spots in the whole state were inside waiting to be discovered, along with some helpful diet tips and a list of five up-and-coming companies in Charlotte owned by women.

“Terrific,” I muttered. Rather than flail around again, I flipped it open and hoped Miss Moore would be done soon.

I was on the fifth most romantic place in the state—the beach near the Hatteras lighthouse, if you must know—when her footsteps sounded on the stairs. Moving fast, I tossed the magazine back on the table, then leaned back and closed my eyes like I was taking a nap.

“Number four is the Grove Park Inn, up in Asheville,” she said from right behind me. “I don’t agree with their top three, though.”

“Hmm?” I asked. “You don’t say.”

“I do say,” she corrected me, “and you’re not the only man I’ve spotted pretending not to read that. More men read it than women. I think they’re trying to do some scouting, or maybe get some ideas.”

“Not me,” I told her, and I flung myself out of the chair. “It was a simple matter of physics.”

“Physics?”

I walked around the chair and gave her my best sheepish grin. “Yeah. I couldn’t reach any of the others.”

She gave me a quick little smile, then pointed to the door. “Go on outside,” she said. “I need to lock up and turn off the lights.”

“I won’t stop you,” I promised, and I headed out the door. Behind me, she straightened magazines, flicked off light switches, and shut down the computer. Through it all, she worked with a tidy efficiency that wasn’t so much graceful as it was precise. For Miss Moore, it seemed, if it was worth doing, it was worth doing as quickly and as neatly as possible.

Meanwhile, I leaned up against the outside wall and watched.

It took maybe another five minutes for her to finish up. She came bustling out the front door, apologizing for having taken so long. I laughed and told her that she was doing me the favor, and that she could take all the time—I nearly said “damn time” but caught myself—she wanted.

“Don’t say that,” she told me. “I just might.” Then she locked the door and tugged on it once to make sure it held. It did, so she pivoted and started walking to her car.

It was easy to spot, as it was the only one still parked on the street. The sun was still well above the horizon, but the town had the feel of having gone to bed right after supper. Off in the distance you could hear cars, no doubt headed for one of the two bars or maybe the movie theater (all of three screens now, Sam had told me on our first trip in). Here, though, things were quiet.

“Hop in,” she said. She pressed a button on her keychain to unlock the doors. It was some kind of Chevrolet, sensible and small and what the advertising boys called “sporty,” which meant that it didn’t have much in the way of trunk space. There were compact discs all over the front seat, for which she apologized, and a half-full bottle of Cheerwine in the cup holder.

“I wouldn’t drink that if I were you,” I warned as she settled into the driver’s seat and pulled the seat belt across herself. “Cheerwine that’s been sitting in the sun makes people hallucinate, shiver, and perform interpretive dances in public.”

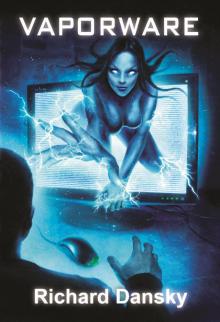

Vaporware

Vaporware Firefly Rain

Firefly Rain