- Home

- Richard Dansky

Firefly Rain Page 22

Firefly Rain Read online

Page 22

Steeling myself against the pressure inside, I ducked back into the kitchen. After a gulp of cold coffee for courage, I called. The phone rang twice before Carl picked up, which is to say about two rings sooner than I was ready for him to.

“Yeah?” His voice was hard and suspicious, like he’d been waiting for the call and wasn’t happy to be getting it. “That you, Logan? Speak up.”

“It is, Carl.” I swallowed and pulled together as many of my thoughts as I could. “I need to talk to you.”

“Well, I don’t need to talk to you none. What happened, you eat all your damn food already?”

I felt my lips curling into a grin. Same old Carl, which in its own way was a comfort. If he’d gone soft on me, I would have worried. “No, Carl. I’m doing fine. I just wanted to talk. I wanted to say thank you, too, but mostly I just wanted to talk.”

“Thank you. Heh.” His laugh sounded like dry leaves. “Nice thing to say, especially when you’re trying to butter a man up. Don’t thank me, Logan. I’m just doing my duty.”

I crossed the kitchen and tucked the phone under my chin. “Your job ended when I came back, Carl. You’ve gone way above and beyond, even if I don’t understand why.”

He laughed again, without any joy in it. “That was a job, boy. I keep telling you that. Now why don’t you stop dancing round the subject and tell me why you want to bend my ear?”

I felt a small jab of anger twist me up inside, as much from surprise as from hurt. I guess I really had been trying to say thank you, once I’d thought on it, and Carl’s dismissing it made me feel low. “I really do want to say thank you, you know.”

He snorted. “If you did, you’d say it to my face, not when you’re hiding behind the phone and piling up questions to toss at me. Don’t play hurt, boy. It doesn’t become you. Just ask your questions straight and you might get an answer. You’d best hurry, though. I ain’t long on patience these days.”

My neck had a crick in it, so I switched the phone to my other ear. “Fine, if that’s how you want it,” I said, and I tried to phrase my questions in a way that would draw answers, not whip-crack derision. “Look, I think I’ve got some idea of what’s going on here. Maybe not with Hanratty or the car, but with the house, at least. I know you won’t talk about that promise, so I’m not going to ask. I think I know why you wanted to talk to me down in the Thicket, though I’m not sure exactly how. But now all of a sudden things are getting mean here, and I don’t know why. There’s something wrong, and I want to make it right. How can I do that, Carl?”

There was almost silence on the end of the line, just slow breathing coming down the wire. “Boy,” Carl finally said, “I’m not sure.” More silence. “You remember what I told you down in the Thicket?”

“Yes?”

“You think on that real hard, son. Think on it the next time that pretty librarian smiles at you.” He paused, and I could feel the tension in him as he tried to figure out what he had to say. “And I got a question for you.”

That brought me up short. “For me?”

“Unless there’s another jackass named Logan on the line, I’d reckon so. Now think about this, ’cause you’ll only have one chance to answer it right. Get it wrong and, well, I wash my hands of you. I done my best.”

“No pressure, then,” I wisecracked. He didn’t laugh, not that I had expected him to. “Hit me.”

“Something’s gonna hit you, all right,” he said dryly. “Just answer this one for yourself. You don’t need to tell me nothing. Think about your father, and ask where his place was.”

It didn’t surprise me when Carl hung up without saying good-bye.

I sipped more cold coffee and thought about the question. The more I did, the less it made sense. When my grandparents had died, the house had passed to Mother and Father. It was theirs. The deed, I knew, had been in both their names. The house had a sense of being solidly theirs, Mother’s decoration over the base laid down by Grandfather Logan. No, it didn’t make any sense. I put my coffee cup down on the table and steepled my hands under my chin. Whatever the hell Carl was talking about, it was too much for me, at least at this hour of the morning. I folded my hands and stared down at the tabletop. It really was damn ugly, now that I thought on it.

I blinked. That couldn’t be it, could it? Every piece of furniture in the place was either inherited or picked out by Mother, except the table. Surely that couldn’t have been what Carl meant. A quick look around the kitchen convinced me that the hunch wasn’t quite right. It was very much Mother’s room, really, and the more I thought on things, the more I realized that they all were. Her touch was all over, from the front room to kitchen counters to the setup of the mudroom in back. This was her house, top to bottom.

Or maybe not. Toy soldiers told me differently, and the notion hit me like a thunderbolt. The one place Mother never went, the one place Father kept as his own—that was the attic.

Without thinking, I rose up out of my chair and walked down the hall to the attic entrance. That white string dangled in front of me, flapping in some draft I couldn’t feel. It reminded me of the lure on one of those deep-sea fish that look like aliens, or monsters. Those things had always held an awful fascination for me. I’d had nightmares about them as a child, imagining giant ones lurking in the ponds and waterways near the house, waiting for me.

I still took the bait. Reaching up, I yanked the cord down. With a squeal, the trapdoor opened toward me. My left hand held it steady, and my right let go of the cord to pull the ladder down. It looked old but sturdy, the wood dark with age and never painted. The steps seemed strong enough to hold my weight—they’d held Father’s, after all—and so I trusted to luck and revelation, and I went on up.

It was smaller than I remembered, and the air was thick with dust. A naked bulb swung down from the ceiling, a chain hanging down from that, and that was all the light to be had up there. Two or three clicks were needed to get it going, and even once it lit up, it looked distinctly unwell. Hurrying seemed sensible.

A quick look around showed me boxes and dust. There were no footprints here, nothing that looked like a disturbance at all. Another time, I’d ponder that, wonder how whoever had gotten the soldiers down had done it without setting foot up there. That was for another time, though. I was hunting the scent Carl had given me.

Patchy insulation lined the ceiling in places. In others, you could see the nails from the roofing driven straight through. They stuck out like thorns on a briar, and I reminded myself not to bang my head. Doing so would be unpleasant.

Something tugged me toward the far end of the room, and I let the feeling pull me along. That was the spot that had always been forbidden, even after I’d been old enough to reach the cord. Father had kept his things here in a locked trunk, the pieces of his life that no one else had been allowed to see. I’d tried getting in once, thinking in my idiot teenager way that he’d been hiding dirty magazines, but the lock on the trunk had defeated me. Father had found out somehow, and that was about as angry as I’d ever seen him get. I’d never tried it again. Even when Father had died, I’d left it alone. It was, I suspected, what he would have wanted.

This time, the lock was off. The trunk sat there, massive and black, and waited for me to open it. So I did.

Inside were papers, neatly bundled and tied off with red ribbon. Clothes, folded and tucked into plastic bags to protect them. Toys, ones I’d never seen. A baseball glove and a beaten-up ball, signed illegibly. Old pictures wrapped with rubber bands. And tucked in with the rest, a small book, bound in leather and tied around with a cord. A folded piece of paper poked out from one side. It was white and new, not yellowed like the rest that I saw.

This was what I was here for, I knew. Carefully, I pulled that book out, and closed the lid behind it. There’d be time later to go through those things, maybe getting to know Father a little better in the process. I found myself looking forward to the prospect.

Right now, though, I had something

to read.

I moved back toward the light and sat myself cross-legged on the floor. Carefully, I untied the leather cord. The book fell open to display pages filled with Father’s handwriting. The paper, though, was marked with Carl’s.

Jacob, it read, and I realized with a shock it was the first time I’d ever seen him use my proper name, You’ll no doubt find this when the time is right. I don’t know what your circumstances are, or if you’ll ever come back to see this, but certain promises have been made that I believe will be fulfilled. Have a little faith, and read what your father has to say. Make of it what you will. The rest is up to you.

Below, it was signed in his hand, an economical collection of letters with as few curves as he could manage. I folded the note over twice, then tucked it in my shirt pocket. Then, sitting under that sickly bulb, I started to read.

nineteen

Father’s book was not, much to my surprise, a day-by-day accounting of his doings. Instead, it was more of a journal, a collection of random writings. They dated from when he was fifteen or so to the years just before his death. The book itself was maybe an inch thick, made of heavy paper that was rough-cut on the edge. The cover was worn but sturdy, and the binding was stitched. This had been made by a man who wanted things to last, and owned by a man who took care of the things that were important to him. Even now, the leather of the cover was supple.

Not knowing what exactly I was looking for, I thumbed through the book. The earlier entries were in pencil, later ones in ink. There were essays in there, and bits of poems both original and quoted. There were song lyrics and a few sketches that looked better than I would have guessed, including one of Grandfather Logan looking younger than I ever remembered seeing him.

Mostly, though, it was just observations on life and the things Father had seen. And so, lacking any better place to start, I turned back to the beginning and started reading.

He’d wanted to get away when he was young. That much I’d known. What I hadn’t known was that he’d done it.

The words he had for Grandfather Logan weren’t kind. Cold was one of them, stern was another. He had respect for his father, but not a lot of love that I could see, and he couldn’t wait to leave the house and the land.

I rubbed my eyes for a moment and winced. Some of the words Father used could have come out of my mouth, save one: respect. I never felt much respect for him, just confusion and anger. I could sense Mother’s growing frustration with him, and I made that my own. I couldn’t get away fast enough, and I couldn’t imagine a worse fate than being like him.

It seemed I was, though—or at least that I walked some of the same roads he did. College for him was Chapel Hill, not Boston a thousand miles away, but it was somewhere else and that was good enough. He went, and he took his own sweet time getting back while Grandmother and Grandfather Logan patiently waited. Those years were a blur of notes—a sketch of a street scene in Paris, some time in New York, mentions of women known and women lost. There was no mention of his work, though, or of Mother.

That changed when he came home. He came home after seven years away, grudging the time and the necessity. Grandmother Logan had fallen ill and would die soon after, but even so there was an air of wariness in the places where he discussed it. He loved his mother, yes, but there was something about coming home he dreaded. It wasn’t enough to keep him away, though. In the end, he came back to see her and say farewell, intending to make a short visit and then go.

Instead, the next twenty pages were about Mother. There was no more talk of returning to his wandering ways after that, just occasional wistful notes on things he wished he’d been able to see again.

I stopped at that point, frowned, flipped back, and read some of those passages again. He’d said something that nagged at me, and I was nearly frantic by the time I found the page I was looking for again.

It seems, he’d written of Mother, almost like she’d been waiting here for me all along.

I paused at that. What if she had been? What if she’d been the hook set in Father to reel him in and keep him here?

Who’d done it, though, and why? Not Mother, certainly—at that point she hadn’t known him, couldn’t have known him. But if not her, then who?

Something cold started crawling up my spine as I thought about that question. Who’d wanted him back? Grandmother Logan? Maryfield itself? Who’d needed a Logan on this land?

I shook my head, trying to deny the thought. I was seeing ghosts and powers again when there was no need to. What if he just really loved her? Judging by those twenty pages, he did. I didn’t have any answers, so I read on, looking for them.

I found the first mention of myself about ten pages on from that, and nearly stopped. No man wants to know what his father really thinks of him, because every man fears not measuring up. As long as he can hear “I’m proud of you,” the rest is just noise.

For years, I’d told myself I didn’t care what Father thought. It’s why I tried to avoid thinking about him. Now, facing the truth of it, I knew those words were a lie.

Afraid of what I’d see, I turned the page.

And there it was in black and white, impossible to disown or deny. Disappointment. Dreams and wishes left unfulfilled. Self-doubt as he wondered if he was being a good father to me, pain as I drifted away from him, anger as he saw the contempt in my eyes. Woven through that were the growing seeds of discontent with Mother—the doubt, the worry, the feeling of being displaced in his own home.

He didn’t talk much about the way he gained weight. I think it was just something Mother disapproved of, and that nearly broke my heart.

I read on, and my name disappeared from the pages. He talked about the Thicket a few times, about how he felt compelled to leave it be and the grief he took for that decision. He talked about missing me but once, and those words were laced with a faint hint of envy. He’s gotten away like I thought I had, Father wrote. His mother misses him terribly, and wishes every day he’d come home already.

And toward the end, there was much said about Carl. He and Father were never friends, that much was true. Carl was a suitor for Mother’s hand when Father swept back into town and whisked her away, and Carl never forgave him for that. He was Maryfield through and through, a son of the local soil who couldn’t imagine stepping past its borders. The years softened and transformed his love for Mother, though, and through that Father and Carl made their peace. Father saw his end coming and wanted someone there for Mother and for the land. Carl accepted the responsibility—did it out of love for Mother and respect for Father’s being humble enough to ask. They even talked about me once. Carl said that Mother was afraid I’d never come back. Father was afraid I would, and that I’d never get away. He was proud of me, he wrote, proud of what I’d started to accomplish. He didn’t want me to come home and stay, abandoning all I’d worked for.

Left unsaid was that he did want me to come home, if only to say good-bye. Left unsaid was any thought of his leaving the house to come and see me. That never seemed to be a possibility. This was his place, and he was bound to it.

Toward the end, he speculated a bit on things, on how he’d come home and why. He spent more time in the Thicket then, even though it was hardly an easy thing for him to do. There was nothing of what I’d expected, though. I’d read too many bad novels, I guess—I wanted there to be talk of ancient Indian burial grounds on the land, or curses cast or ghosts that haunted the place when Father was young. I’d wanted a mystic formula to give Mother peace, or a way to protect myself from her disappointment and anger. None of that was there. Father had been an investor, and a clever one, not a wizard or a shaman. He’d had his dark suspicions on why he’d been called home, but he hadn’t wandered far down those paths. Instead, there was just a brooding feeling over how the spirit of the place didn’t like its sons to wander, and a couple of jokes about the carrot and the stick.

I thought about my car, and about Adrienne, and about falling shotguns and the dog out

side my door at night. Carrot and stick, maybe. The picture was still too blurry for me to see.

Too quickly, I was at the end. I turned the last page and didn’t see what I’d hoped for. I’d wanted to see a note from him to me, a farewell or a benediction or an answer. Instead, there was a simple note in a shaky hand. Elaine judged a man by his promises, he said, and I’m afraid I haven’t kept mine. I didn’t put the stars on a string for her and I didn’t pull down the moon to put it in her hands. I didn’t take her to see Paris, though I got the feeling she never wanted to go. I didn’t raise the son she wanted, or give her the daughter she would have loved. And I’m not sure I always loved her, though here at the last I find I still do. God have mercy on my soul and understand that I did the best I could, and forgive me for the times I fell short. Maybe some day I’ll have the right words to ask her forgiveness as well. Then, down at the bottom, Here’s hoping Carl has more sense than I did.

That’s where it ended. I closed the book, almost reverently, and tied the leather around it again. I was tempted to put it back in the trunk, but instead settled for taking it with me as I climbed down, feeling sad and angry and a little bit afraid. I was going to need to read it again, that much was certain. Maybe this time I’d find more of what Carl had hinted was in there. That last page nagged at me, nagged at me hard, and I knew the answer was close. My feet hit the floor of the hallway, and I absently folded up the ladder and closed the trapdoor.

Only then did I remember that I’d left the light on in the attic. Madder at myself than I ought to be, I reached up for the cord to pull the door back down. I’d just about reached it when I heard something that made my blood run cold.

Up above and undeniable, I heard the click of the lightbulb’s chain as something gave it a tug. The light disappeared from around the edges of the trapdoor.

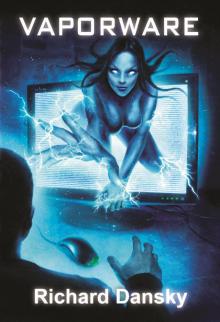

Vaporware

Vaporware Firefly Rain

Firefly Rain