- Home

- Richard Dansky

Firefly Rain Page 28

Firefly Rain Read online

Page 28

“You don’t know anything,” Carl finally said, when the last flutter of wings had died away. “You’ve got all the pieces in your hands and you’d rather line them up by which has the prettiest picture than try to put them together. Think about something bigger than you for once, boy.” The last word was filled with venom. “You’re right, your parents are still here, and that’s why I’m here, too.”

“The promise,” I said, realization washing over me. “You promised them you’d take care of me.”

“No.” His voice was cold and flat as stone. “I promised your mother I’d see you back here and set you up proper. Make you see that this was where you belonged, even when my gut told me that wasn’t necessarily so. And all the time, she was there watching. You got no idea, son, none at all.”

My eyes met his. Neither of us looked away. For a moment, it was as if there had been only the two of us there in that circle. “You’ve done your job, Carl. You’ve kept your promise. Now let me make my decision. Let me go.”

“I’m afraid I can’t do that,” he said, and he looked away. “What she wants, she gets. You know that. She wants you kept here. You got no choice at all.”

“It’s a house, Carl. I can just walk away.”

“You think that, don’t you? What are the odds something hasn’t happened to your friend’s car by the time you get back from this place? If you try to walk, what makes you think a wind and a rain won’t come up and drive you back into the house? Call for a way out, and that phone line will go dead. You should just be thankful she didn’t ask me to cut it before.”

I walked toward him, getting angrier with every step. “What the hell are you talking about, Carl?”

He set the lantern down and crossed his arms over his chest. “You know damn well what I’m talking about, boy. I’m talking about keeping you locked up in that house while she had time to work on you, to hook you and drag you in, to make you want to stay and think it was your idea all along. I didn’t steal your damn car, boy, but I damn sure made it so you couldn’t track it down once she had your father take it. Brought you food so you wouldn’t leave the house, tried to keep you inside those walls so you’d settle in ’cause it was the only thing you could do. Don’t go looking for that cell phone in the tall grass, neither. You won’t find it no more. Hell, I had to talk her into letting you go into town at all, and then I was only able to ’cause it was a way to get you into that pretty young thing’s arms. Don’t you see, son? You’ve been given every chance to go along with this. Why keep fighting?”

I shook my head. “And the time I almost got led to my death? Who was driving the car that day, Carl? How’d you know to find me?”

“You were supposed to take to your sickbed, Mr. Logan,” Reverend Trotter interrupted. “And someone from town would come to tend you. Unfortunately, you seem to have inherited the Logan family constitution.” He looked thoughtful for a moment. “Your father was a tough bastard before you, you know. We had much the same problem with him.”

I turned to face him. “That’s not in the book.”

“Oh, yes it is.” He nodded solemnly. “If you know how to read it. Understated man, Joshua was, and in his way as stubborn as you are. But in the end, he realized he belonged here, and in exchange for his acceptance, he received a few… dispensations. Like the love of your mother, for example.”

“That’s impossible. Stupid. And even if Carl’s trying to keep some bullshit promise”—Asa snarled at that, and Sam didn’t seem too eager to calm him this time—“Why are the rest of you here? Is this the secret town council? You going to show me the dark rituals that only I can perform, as the last of the Logans? Come on, give me something better than that.”

“It’s not quite that,” Hilliard said, “but there’s a little truth to it. The town doesn’t like giving up its own, you see, but some folks belong here more than others. Logans belong here,” he said, and his eyes met mine, “the same way that lady friend of yours doesn’t. And sometimes, well, when the circumstances are right, the town can take more of a hand in things.”

He shook his head, sad for me, or maybe for himself. “Your mother was out here a long time by herself. I think the land learned to listen to her, or maybe she listened to it, the same way it talked to your grandmother back in the day. It doesn’t matter. You made her a promise that you didn’t keep, and that gave her something to cling to. Carl made a promise he did keep, and that’s why we’re here. We’ve all made the promise, too, Jacob. Told your mother we’d help bring you back. She insisted on it, really—there should always be a Logan on Logan land, and she was quite the traditionalist. Helped her adjust to life with your father, to be honest. And believe me, it’s a promise we’d all rather be shut of.”

“It’s just a promise. Words.”

“That’s what a promise is to you, boy, and that’s what brought us to this place.” Carl’s words were full of scorn. “You gave out promises free as air and never kept a one. Fair broke your mother’s heart, you did, always promising to come home and never doing it. She lived on that hope for years, and you let her wither on it. Promises have weight, boy. They have consequences. And if you make ’em the right way, to the right person, they’re stronger than death.”

I opened my mouth to scoff, but Hilliard interrupted me. “Carl’s got cancer, Jacob. Doctors said it should have killed him years ago. She wouldn’t let him go. Reverend Trotter? His heart’s bad. Dead tissue, they said. Shouldn’t be able to keep beating. She makes sure it does.”

“And you?” I said softly.

“Don’t ask,” he replied in a way that filled me with shame. “Death would be welcomed in my house, at any hour of any day. But she’s not letting us go until the deed is done.” He looked left, then right, all around the circle. “You can help let us go.”

I blinked hard, tears doing their damnedest to fill up the corners of my eyes. “It’s impossible. This is Mother, right? The little woman who couldn’t get Father to stop eating, couldn’t get me to come home. How can she do this?”

“That was all you ever saw of her,” Reverend Trotter corrected me gently. “That’s not all she was. She was a strong woman, and a brave one, except maybe where you were concerned directly. And death changes people, changes them more than even you’d think, especially when you’re trapped someplace you don’t belong. Bargains are made, you see. Deals are struck. Prices paid.”

“The fireflies,” I breathed. “Oh God, the fireflies.”

“The fireflies,” the reverend echoed.

“Makes you feel good, doesn’t it?” That was Sam Fuller, his eyes full of hate. The force of it hit me like a shot to the gut, the pure brute fury of it. I’d been wrong to think we could ever be friends, not with that kind of hatred in him.

Not that I wasn’t sure I didn’t deserve it.

He took a step forward, stalking me. “You ever think on what you did, Logan? Ever think on what it cost? Brave man, to shoo the fireflies off her stone? Well, they’ve been waiting to do their duty. Been waiting ever since, and your folks been waiting with them.”

I took another step closer to Carl. His gaze measured me up and down, registering what I was doing, but he didn’t move. “Why do you care, though, Sam? My sin, not yours. My parents”—the words were oddly hard to say—“not yours.”

“My friends,” he answered simply. “My neighbors. Waiting on your mistake. And when I got to talking with you and realized you didn’t belong here, I realized that all these good men had suffered for nothing, and I’d be suffering along with them.” He scratched Asa under the chin. “There’s two ways to bind you to this place, you see. Two ways to seal the bargain. Love and blood. We’ve been trying both.” He looked away. “The love was Adrienne’s. The blood was supposed to be Asa’s. You haven’t taken either.”

“My God, Sam, I’m sorry. I’m so sorry,” I said, and I turned to look around the circle. “All of you, I am so goddamned sorry. I wish I’d known. I wish—”

“Y

ou made your promises,” Mr. Hilliard rumbled. “You did know, deep down. You always knew.”

“So how do I make it right?” I asked. “What do I do?”

“Two ways to make it right,” Carl answered, his toe kicking at the edge of the lantern’s base. “The pleasant way is to go back up to that house and whisper some sweet words to a kind girl who’s asleep.”

I shook my head. “No. If I court her, I court her myself. Not like this. It ain’t fair to her, same as it wasn’t fair to my mother.”

Carl shrugged. “Then there’s one other way. Sam?”

Fuller stepped back, away from his hound. Asa sat there, docile, his tail thumping the ground in slow, measured beats. “I’m ready,” he said, his tone giving the lie to his words.

“Asa?” I asked.

Fuller nodded. “Kill him. Now. He won’t fight.” He shuddered, fighting back what sounded like a sob. “Only reason he went bad on you was to try to get you to shoot him. Make you do it in self-defense.”

“No.” The murmurs rose up around me, confused and angry. “I’m not doing it.”

“You ain’t got but two ways to do it, son,” Carl said. “And if you won’t take the easy path, you need to take this one.”

“Why didn’t you let me shoot you, then, the last time we were down here?” Carl flinched at that, and I saw an opening and kept right on pushing. “Why’d you dodge when all this could have been over, and no one the wiser?”

He stood there, suddenly frail. But only for an instant before the Carl I knew was back again, my tormentor come to lead me the last mile. “Killing me wouldn’t have done it,” he said softly. “My blood’s not quite right anymore. The sap from a dead tree won’t flow right, if you take my meaning.”

“Or maybe you weren’t quite ready to give up living yet,” I said, trying to sound braver than I felt.

“If only,” he said, and there was a world of heartbreak in those two words. “Now which will it be? You get to decide here, and you’ve got to decide now.”

“Bullshit,” I spat out into his face. “I can go right back to that house and decide for myself if I want to stay, without any magic fireflies or sacrifices or supernatural shotgun weddings or any damn thing else. I ask that girl to marry me like this, and in thirty years the same thing will happen all over again. And I’m not killing my neighbor’s dog, not with him standing there and not for this. It’s a wicked thing to ask of a man.”

Carl smiled and nodded, and then he decked me. I went over like a sack of bricks, the book flying out of my hand. “That’s very noble, son. Damn stupid, too. Is a dog’s life worth more than a man’s?” He stepped forward and delivered a kick to my ribs that knocked the breath out of my lungs. “Is it maybe worth holding your mother’s immortal soul out of Heaven?”

I scrambled to all fours, just in time to get a boot under the chin. My head snapped back and I tumbled to the edge of the ring. Strong hands shoved me back into the center, back toward where Carl was waiting. Behind him, Asa sat calm as a statue, watching.

“It’s not right,” I cried out, and I took a swing. Carl ducked under it and planted his fist in my gut. I doubled over, and he brought both hands down on the back of my head. I went down, my chin hitting the ground hard enough to rattle my teeth.

Around us, the other men in the circle were strangely silent. No cheering, no shouting, not a word of encouragement or dismay. But every time my back brushed the outside of that ring, they pushed me back in.

“You angry yet, boy?” Carl taunted. “Angry enough to fight?” I didn’t answer; I threw a series of punches at his torso instead. He blocked them all but missed the straight kick I leveled at his knee. It staggered him and drove him back, but it didn’t wipe the grin off his face. “Angry enough to get your hands dirty?” I rushed him to press the attack, but he met me with a flurry of punches. I blocked some of them and caught some others in the face. The taste of blood filled my mouth; I spat once and lowered my shoulder into Carl’s rib cage.

He was light enough to go over easy—the cancer, I guessed—but getting him down was one thing, holding him down was another. He got his arms up, one hand on my windpipe, and we rolled around on the ground, kicking and gouging like wildcats. He choked off my air; I hacked at his wrist and bent his bony fingers back. He went to gouge my eyes; I slammed my forehead into his and snapped his head back.

“Good, boy, good,” he muttered with a bloody grin, and then I was somehow on top of him with my forearm across his throat and his right hand pinned down into the grass. He smiled up at me. “You’re ready to do what you have to do.”

“I’m not going to kill, Carl,” I told him.

“Oh, yes, you will,” he assured me. “Or I’m going to kill you and keep you here that way. She’ll be happy with that, in the end.” With his free hand, he pointed up to the night sky. I looked up. Thousands of fireflies danced there, perching themselves on tree branches and casting a glow that didn’t dare reach the ground. “You’ll do it with them watching, because you’ll do it to protect yourself. I just proved that—to them, to you, to everyone.” He looked slowly around the circle. “And if I’d kept pushing, you’d have kept swinging. It’s in you, Logan.”

“No, it ain’t.” I rolled off him and pulled myself to my feet. My ribs ached, and my face was covered with cuts and scratches. My mouth was filled with blood, and the knuckles of my left hand were scraped raw. Carl, down there on the ground and smiling like a skull, didn’t look that much better. “If it were in me, you’d be dead right now.”

“I just didn’t push you hard enough,” he said, and he coughed. Slowly, he got to his feet and planted himself in front of me. “You fought pretty hard anyhow, and that’s just for your worthless skin. What’ll you do,” he asked, and he looked past me, past the ring of men, out into the Thicket and uphill, “to protect someone else?”

“No,” I said. “Don’t.”

He ignored me. “Sam?” was all he said.

“Of course,” Sam replied. “Asa, go get ’em.”

Asa’s eyes went flat and cold, and that green light sparked in them. He growled low in his throat, and then he leaped forward, teeth bared and spittle dripping down. I braced myself for the hit, threw my arms up in front of me, and waited.

He bounded right past me, howling, and out of the circle. In an instant, he was lost in the underbrush, headed uphill.

Headed toward the house.

“Son of a bitch,” I swore, while Carl cackled behind me.

“That’s it!” he said. “You’ll spill that blood now, won’t you? Go git ’im!”

“You bastard,” I said, suddenly calm with the knowledge of what I had to do, and I reached down for the Coleman lantern. “You fucking bastard.”

“You won’t need the light,” he said, still grinning. “Just follow the sound.”

I swung.

The base of the lantern caught him just under the jaw with a solid crack. I could hear bone snap, could see things moving under his skin that weren’t meant to move that way. He spun around once, eyes wide with surprise, and fell to the ground.

I stepped over to him, and then I swung it again. It connected with the side of his head, and this time, the sound it made was a grinding crunch. I didn’t care. I just held up that lantern, burning bright through all that, and stared down at the wreck of Carl’s face.

“Maybe it is in me after all,” I said. “Fine. I’ve shed blood. Now call him back.”

“Can’t,” Sam said, but he didn’t move. None of them did.

“Like I told you… can’t be… my blood,” Carl wheezed. “Mine’s already… spoken for.” And he laughed—a horrible, wet sound.

“You’ll be wanting this.” Hilliard stepped forward and handed me the length of wood he’d been holding. “With Asa, it might come in handy. The lantern’s too heavy to run with, anyway.”

I took it and looked up at him. “Time’s a-wasting,” he added, and he pointed to Carl. “We’ll stay with him. Don�

�t worry about that. Now go do what you have to do. For your mother, for your father, for those women in that house. For all of us. Go.”

“Go,” they all murmured as one, and the back of the circle opened for me. In the distance, I could hear Asa howling.

The lantern fell from my fingers and rolled onto its side. I spun around, looking at each and every one of those men, looking for another way out of this. Their faces told me there was none. My eyes finally met Reverend Trotter’s. He stared back at me, sad and knowing. “Son,” he said, “God go with you. Now run.”

I ran.

twenty-two

This time, the trees seemed to be holding me back. Up ahead, I could hear Asa. His howl was enough to wake the dead, and he gave it often, leading me on. Sometimes it sounded like it came from behind the next tree, sometimes from a mile away.

I was pretty sure he was waiting for me. I didn’t trust that hunch enough to bank on it, though, so I ran. Ran with my head down and that walking stick Hilliard had given me tucked under one arm, ran through the creepers and the vines and the low-hanging branches that caught my clothes and tore at my hair and pulled me back, ran even when I didn’t know quite where I was running to except in the direction of that howl.

Suddenly, I was out of the trees and looking uphill at the line of pines that hid the house from view. My breath rasped in my lungs, hot and painful as I stood there a moment. Around me, the fireflies rose up in a swarm, lighting my way. Halfway up the hill, I could see a dark shape moving fast. Moving toward the house.

Asa.

I started running again.

The cloud of fireflies moved with me, casting long green shadows on the grass. I ignored them as best as I could, throwing myself up the slope. Up ahead, Asa vanished around the bend past the pine trees and closed in on the house proper.

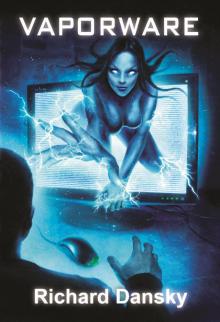

Vaporware

Vaporware Firefly Rain

Firefly Rain