- Home

- Richard Dansky

Firefly Rain Page 4

Firefly Rain Read online

Page 4

I stood there and watched him go. He drove off quickly, his truck raising a trail of dust behind it as he sped off down the road, back to town. Meanwhile, my car, the car I’d been so proud of in Boston, just sat there, immobile and useless. It looked ugly and out of place, and I suddenly felt the same way.

“Well, do something,” I said to the lump of machinery sitting there, more out of frustration than anything else. It didn’t respond, not that I’d expected it to. I stared at it a moment longer, then went inside to see what Carl had brought me.

It was obvious, I saw after I unpacked the sack of groceries Carl had provided, that he didn’t think much of me. There was no beer in that bag. That much had been obvious when he’d set it down on the counter without the reassuring clank or clunk that you get from bottles or cans. Instead, there was a gallon of milk and, tucked in next to it, a squeeze bottle of Bosco.

I felt my cheeks get hot with embarrassment. Milk and chocolate syrup? I slammed the Bosco down on the counter and ripped open the icebox door. It swung open hard enough to bounce back and catch my arm on the elbow as I tried to shove the milk in. The pain nearly made me drop it, which would have been a disaster. I could only imagine calling Carl again to explain that I’d spilled the milk he’d brought me, and could he please fetch me some more? I’d be able to hear his laughter without the phone, and so would have half the county. The thought was unbearable.

Moving with considerably more caution, I put the milk on the top shelf and the Bosco on the bottom. No sense leaving the two of them together to get any ideas, after all.

I turned my attention to the rest of the bag, the contents of which proved considerably less inflammatory. There were a few packages of Oscar Mayer cold cuts, a loaf of bread, some eggs (which sat miraculously uncrushed down at the bottom), and a few other essentials. A tin of instant lemonade mix was the heaviest thing in there, sandwiched between a fat stick of butter and some sausages. Some cans of beans and a couple of thin, tough-looking steaks wrapped in butcher paper rounded the whole thing out.

In my head, I added the whole thing up and gave a low whistle. It wasn’t exactly gourmet fare, but it still had to have cost Carl a pretty penny. And he said he’d be coming back in a few days with more.

It didn’t add up. Or, more to the point, it did add up, and it would keep adding up. I had paid Carl nicely to keep the house in good repair, but not to keep me fat and fed. And as for that promise he’d mentioned, well, the less I thought about that particular statement, the happier I was. Sighing, I washed out my empties and put them in the paper sack, then put it next to the trash can. I’d recycled in Boston. Here, I was just getting them out of the way.

five

Morning came slowly after another sleepless night, and the car was no longer where I’d left it.

I found myself standing out in front of the house, too angry to speak. The car was gone. Sure, I’d been five kinds of fool to have left the keys in the ignition, but that car hadn’t been capable of moving under its own power, keys or no.

And now it was gone. Somehow, some way, someone had come in the middle of the night and taken it out of my driveway without so much as a whisper or a rattle. Hell, if I hadn’t known better, I’d have thought there’d never been a car there in the first place. The empty spot beside the house looked… well, it looked like it was supposed to be empty, not that it made me any more pleased that my car was gone.

And it had happened here.

Here, where I got laughed at for locking my car door. Here, where the front doors weren’t locked except when there was a door-to-door salesman in the vicinity. Here, where this sort of thing was not ever supposed to goddamn happen.

I’d never had my car stolen in Boston, that was for damn sure.

Taking deep breaths, I walked over to where the car had been and stared at the ground. There was nothing of what I was looking for—no heavy tracks that spoke of a tow truck’s presence, no broken glass from a smashed-in window, not even any footprints that weren’t my own. What might have been the Audi’s tracks leading back to the road were so faint that I wasn’t sure they were there at all, and walking their line back and forth a few times didn’t make me any surer.

“This is just plain stupid,” I told myself and went back into the house to call the police. The officer I eventually talked to was polite but not terribly helpful when I finally got him on the line, but he promised to send someone around to take a look at things soonish. Meanwhile, if I didn’t mind, if I could write up a statement on my own, it would make things awfully convenient.

“Of course, Officer,” I heard myself saying, much to my own surprise. “Is there anything else I can do to help?”

“Thank you, Mr. Logan,” he said, “but I think that’ll do it. We’ll let you know when someone’s on their way. Have a nice day.”

“You, too,” I said, and hung up even as my jaw dropped. “Good God,” I said to no one in particular, “even when I was growing up, the police weren’t that fucking Mayberry.” I checked to make sure that I had in fact cut the connection, then added a few more choice curses about goddamn gooder hick cops who wouldn’t know how to do an investigation if it bit them on the collective, fat, Krispy Kreme–loving ass.

As a matter of fact, I got so warmed to my subject matter that I barely heard the noise outside over my ranting. For a second I couldn’t place it, but as I shut myself up to listen, what it was became clear.

Wheels on dirt on gravel, that’s what it was, and as I walked to the window I saw Carl’s battered old pickup pulling in off the road. I ran outside, arms waving to stop him, but he either ignored me or just plain didn’t see me. He lurched to a halt right where my car had been, then swung his long legs out of the cab and came striding around the front of the truck.

“You son of a bitch!” I yelled, even before he reached me. “What the hell do you think you’re doing?”

“Delivering your mail,” he said calmly. He thrust a fat envelope at me. “I took the liberty of cashing the check those insurance people sent you. The folks at the bank remember your mother fondly.”

My jaw dropped and my mind went blank, but my hand reached out and took the envelope. Without thinking, I stuffed it in a pocket.

“You could say thank you,” Carl grunted, then turned away. “Sorry to hear about your car,” he added, striding off.

He hadn’t taken more than two steps before I tackled him. He went down hard, his hands barely out in time to break his fall.

“How the hell did you know about my car?” I howled in his ear. “I just called that in five minutes ago.”

Easy as a duck shrugging off water, he threw me off his back. I landed awkwardly, a whoof of air shooting out of my lungs, and scrambled back. Carl looked at me over his shoulder, and he had blood in his eye. He looked grim as death, and in that moment I knew, sure as Christmas, that he could kill me if he wanted to.

A small part of me thought he just might.

“You get one of those, son, and that’s all.” With a lanky man’s grace, he climbed to his feet. I stayed down in the dust. “It’s a small town. People talk, even police. And you’d best have some proof before you accuse a man of stealing around here. That’s something you didn’t learn at your Boston college, now, is it?”

Without another word, he strode off, back toward his truck. I watched him go, heard the cab door slam and the engine growl to life. He threw it into gear ungently, and I saw the tires on his truck churn up the dust and rock where any clues might have been.

Stop him, a voice in my head screamed, but I didn’t move. Couldn’t, really. He might have stopped the truck, after all, and gotten out, and Lord knows what would have happened next. But I still hated myself for my cowardice.

An uncomfortable pressure in my pocket reminded me of the payment that had brought Carl out here. A whole batch of questions hopped into my mind, most of them about how exactly he’d managed to cash a check made out to me that he shouldn’t have known about in the

first place.

The whole thing stank to high heaven, but I didn’t know where to start pulling at it. So I did the only thing I could, which was stand up, open the envelope, and count the money.

A fat wad of bills was waiting for me when I popped the envelope—sealed so recently that the glue was still wet—open. There was a lot of money in there, more than I expected. I pulled the cash out and riffed through it. Twenties, fifties, hundreds—there was quite a bit of money in my hands, though that would have been true even if it had been all small bills. I did a fast calculation in my head, got a number that had some round numbers behind it, and whistled. With the house long since paid for, it was enough to live on for a good long while. Good fortune had surely smiled on me, at least in this hour. I hadn’t thought my furniture was worth quite so much, but if the insurance company had, who was I to argue? I counted the money again, came up with a number slightly larger than the one I’d guesstimated, and started back toward the house. Whistling.

It was only then that I remembered the conversation I’d had with the man from the moving company. He’d given me a number. I’d agreed to it. And there was far more than that in my hands.

Insurance companies didn’t make mistakes like that, and they sure as hell didn’t give you more money than they said they were going to. Carl, the money, the things I’d been told by that man Douglas—the pieces didn’t even start to fit.

I nearly called the police again right then and there, but common sense stopped me. What could I accuse the man of? Giving me money? Driving into my yard to do so? Stealing a car that couldn’t move? I’d just get laughed at, and I’d had enough of that already. I put the whole matter aside and went back in the house, stashing the money in a biscuit tin for something approaching safekeeping. There was a pitcher of lemonade in the refrigerator—I’d made it the night before—and so I poured myself a glass and thought about chasing fireflies.

If there was nothing I could do about Carl, I reasoned, I might as well chase the other mystery of the place. So very carefully, I took down one of Mother’s old mason jars from a high shelf in the kitchen. I rinsed it out to clear out the dust, then used an old screwdriver to punch holes in the lid. When night fell, I was ready. Jar in hand, I walked up to the road and my property line.

Here the difference was stark and plain. Out in the road, fireflies danced. On my side of things, they didn’t. You could draw the line with a stick in the dirt, and it would be straight and true.

I put the jar down in the driveway and reached my hands out across the line. Slowly I cupped them around a firefly, a poor little fella who was minding its own business in midair. Then, quick as lightning, I snapped my hands shut around it. I could feel it crawling around in there, signaling frantically through the cracks between my fingers.

And slow as I could, I pulled my hands back to my chest. Would it know? I wondered. What would happen when it crossed the boundary onto my land? I got my answer soon enough. As soon as my cupped hands crossed that line, the light went out and did not return. I could feel the little thing go frantic, ramming against my hand as hard as it could, trying to get back to the road.

I was cruel and didn’t let it go. Instead, I held my hands there against my chest for a long minute, until the wiggling stopped. Only then did I open my fingers to find a dead firefly resting on my palm. It made no motion, and its tail lacked the fading glow every child comes to expect. Instead, it just lay there like a thing long dead.

Respectfully, I set it down back in the road. Then I unscrewed the top of the mason jar. With the empty jar in my hand, I stepped into the road and started catching fireflies.

It was harder than I remembered. When you’re a child, you have a knack for these things. Once you get older you forget, or maybe the skill just leaves on its own. In either case, it took me a good half hour to get the dozen fireflies I wanted into the jar, even though the fields were ablaze with them. Maybe they saw what had happened to the other one. I don’t know.

Once the last one went in the jar, I screwed the cap on tight. Inside, the insects flared up like fireworks, one after the other. The light from them was bright enough to read by, or to walk without fear in the dark. One by one they shone out, brighter than even the remembered prizes from when I was a boy. I held them up a moment, just to see them. They might have been beautiful. I don’t know; it’s not a word I ever used much.

And then, careful as I could, I set the jar down on the boundary between the county’s land and mine. The bottom of the jar barely hit dirt before all the fireflies flew to one side like the other was on fire. There they stayed, crawling all over each other and flashing franticlike, fast on and fast off.

I watched for a while, then nudged the jar a half inch farther onto my land. They crammed closer still, lights flickering on and off fast. Every few seconds one would slip and fall onto the unwanted side. As soon as it hit glass, it would scurry back across like a scalded cat, pushing and forcing its way in with the others until another one fell.

Another half inch. There wasn’t space for them all now, and they knew it. One after another they slammed themselves against the glass, against the lid. They tried, wings flapping, legs flailing, but there just wasn’t enough room, not anymore.

Me, I watched until the losers stopped moving and the winners barely twitched for fear of being shifted again. “I’m sorry,” I told them, and I pulled the jar all the way over my property line.

It didn’t take long. Fifteen seconds later, I was pouring dead fireflies onto the ground, out on the road. Not a one recovered like I’d been hoping they would. Not a one moved.

“Goddamn,” I said, and I threw the mason jar off into the night. It hit a rock somewhere down the road and shattered, and I found myself hoping Carl would cut a tire on it.

I had proof now. It wasn’t something about the foliage, or the soil, or anything else a scientific mind might have proposed to me. Fireflies hated my land, hated and feared it. If brought onto it, they’d flee. If they couldn’t flee, they’d die. But under no circumstances would my parents’ graves ever see their light.

The thought started me moving. I didn’t believe the story Mother had told me all those years ago, but I did remember lights dancing on those tombstones. They’d flown over this land once, lighting it up so the angels in Mother’s mind could see it. Something had changed, had changed hard and unkind, and the only place I thought the answers might be was at the foot of those graves.

Wind whispered through the pine trees as I walked past them. The needles rustled against each other like the sound of Mother’s housedress when she walked, soft against the ear. Off at the back end of the property, I could hear the tree frogs calling, high and sharp. Underneath them was the noise of the bullfrogs, deeper and hungrier.

Mother had joked that Father was part bullfrog, especially when he was eating. He stopped finding that funny after a while.

I took the last few steps to where the stones were. Mother and Father were the first ones buried on this land, even though it had been in Father’s family for generations. My great-grandfather had farmed it, and so had his father before him. Fathers passed it down to sons, living here, marrying, growing old, and dying, but not a one had chosen final rest here. A church ten miles distant held most of my ancestors in its cemetery, though a few could be found in long rows of markers at Chickamauga and the poppy fields of France. That’s what I’d been told growing up, and I found no reason to disbelieve it now.

Father chose to be buried here, though, or so I once thought. Years later, I learned it had been Mother’s decision to lay him to rest out back, keeping him near so she might not be so lonely. Maybe she’d felt guilty for the way they’d fought when he was alive and wanted to make it right after he was gone. I refused to speculate. All that mattered was that he was here, and that she was laid to rest beside him.

All this ran through my mind as I looked down on their markers in the moonlight. There was enough to read the inscriptions by, though year

s of heat and summer thunder had long since scoured away the tombstones’ shine. JOSHUA JEREMIAH LOGAN, said Father’s. BELOVED HUSBAND AND FATHER. HE WILL BE MISSED. Mother’s read, ELAINE STOUDAMIRE LOGAN, WIFE AND MOTHER. HER SOUL RISES TO HEAVEN. No dates marked either one. Let the ages try to figure out when they lived and died. Here in this place, they were timeless.

Their graves had been lit by fireflies once, fireflies I’d brushed away sure as I’d killed the ones out in the road. No fireflies lit the graves tonight, though, and if what I’d seen in the mason jar was any indication, they might never light them again.

All around me, the night got still. The wind hushed and the frogs held their tongues. It was silent, quiet enough that I could hear the rasp of my breath and the thump of my heartbeat, and nothing more. I turned and blinked in surprise. Off in the distance I could see the wind moving leaves. Not here, though. The silence was just around me.

And around those graves. I took a step forward, away from that hallowed soil, and then I cast my words out over the fields.

“What do you want?” I asked in a voice just this side of shouting. “Just tell me what the hell is going on here!”

Nothing answered me, not that I’d expected anything or anyone to do so. My words faded into the distance, swallowed up by the silence. I stared after them, and eventually the world came back to noisy life around me. It wasn’t much, just the wind in the pine trees and the frogs in the distance, but it was enough to drown out the beating of my heart.

Lacking anything better to do, I lay down on the cool, wet grass at the foot of those graves and slept.

six

Morning broke and carried away with it the strongest memories of the night’s dreams. Some stayed long enough for me to recognize them, though, and I found myself clinging to those fiercely.

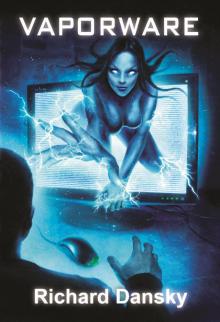

Vaporware

Vaporware Firefly Rain

Firefly Rain